Bridge Programme

Platform ProgrammeThe Construction Innovation Hub’s ‘Defining the Need’ work has generated a cross-Governmental data set that is delivering some surprising new insights into the public sector estate, as well as a solid basis for the design of platform construction systems. Platform Design Lead, Jaimie Johnston – together with Rebecca Wade, co-author of the Defining the Need report – outline some of these findings.

The conditions needed to create the effective, engaged supply chains, high levels of productivity and incremental gains through continual improvement that have allowed automotive and aerospace to flourish are:

Over the past few decades, numerous reports have recommended the adoption of standardised, repeatable solutions as a way for construction to become more like manufacturing and boost its famously low productivity. But this has been difficult to achieve in an industry which has traditionally focused on ‘projects’ rather than ‘programmes’ and is further fragmented by ‘sector’ and ‘discipline’ boundaries.

Addressing this issue requires a broader view than any individual team or client can take. It can only be achieved by a Government client that can look across sectors and take a very long-term view. This is why the Infrastructure and Projects Authority (IPA) set out this vision for a Platform approach:

We will use a set of digitally designed components across multiple types of built asset and apply those components wherever possible, thereby minimising the need to design bespoke components for different types of asset. For example, a single component could be used as part of a school, hospital, prison building or station.

Realising this vision will require the industry to:

Two recent publications show that this vision is now well on the way to becoming a reality.

The first is the Government’s Construction Playbook, which contains a policy to ‘harmonise, digitise and rationalise demand,’ stating:

Demand across individual projects and programmes will be harmonised, digitalised and rationalised by contracting authorities. This will accelerate the development and use of platform approaches, standard products and components.

This key strategy will facilitate the transformation of construction by providing the conditions of sustained consistency that have underpinned the success of the manufacturing sector.

The second is the Hub’s Defining the Need report, the output of a comprehensive piece of work to:

Creating the data sets – and what we found

The importance of (and the challenges faced in) creating a common cross-departmental data set cannot be overstated. Each department has its own nomenclature for spaces and assets and its own way of predicting and reporting its forward pipeline. Getting this data into a granular and consistent format, from which to derive information and insight, has therefore been an important challenge.

The process for spatial analysis, rationalisation and classification was set out in Bryden Wood’s strategy document ‘Delivery Platforms: Creating a Marketplace for Manufactured Spaces’ (Digital Built Britain, 2017). It has taken a concerted effort by the Hub team, working with the Government departments, to deliver this – gathering and processing the data needed to articulate cross-sector needs. As the report states:

This exercise is pioneering in both breadth and scale. It represents the first time that space-level information has been brought together across Government departments, with a five-year pipeline of circa £50bn analysed.

The outputs show why this is such a valuable piece of work, and these are some of the key aspects of the process and the surprising insights that emerged.

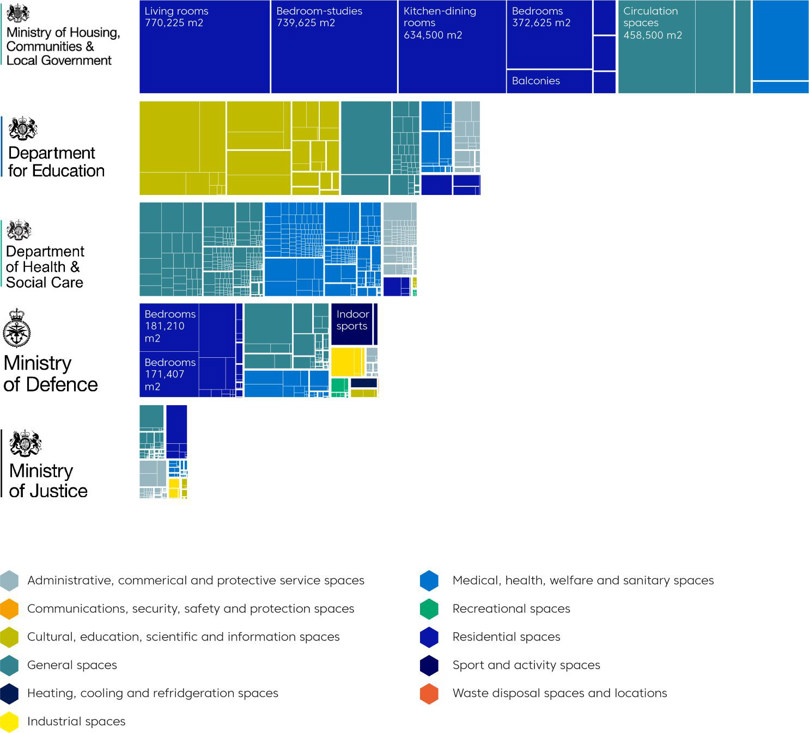

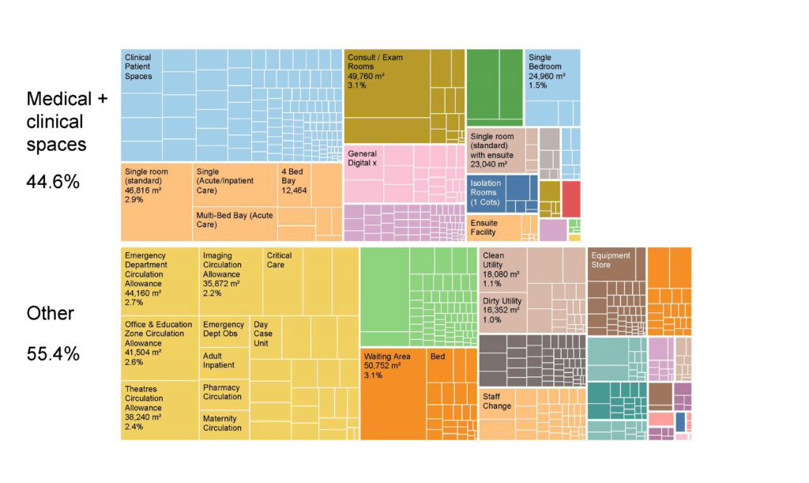

Fig.1 Data visualisation across key Government departments’ 5-year pipeline

Key insights

Finding a common language between departments

One of the key challenges faced by the Hub has been to create a data set which is consistent across departments. It is impossible to carry out even the most basic cross-sector analysis if we don’t have a consistent way of naming spaces.

The Hub team used Uniclass 2015 since it has a consistent format for describing everything from a ‘complex’ at Departmental level (e.g. Co_25_10 Educational complexes) down to a ‘component’ (e.g. Pr_20_29_76_81 Socket screws).

We have primarily focused on space types since this is the level at which most technical performance (related to lighting, acoustics, thermal comfort etc.) is contained.

While we have retained the ‘native’ space names, the Uniclass classification allowed us to filter and visualise the data set at several levels. The power of this becomes clear when we consider an example.

SL_35_80_89 is the Uniclass space code for ‘Toilets’. Being able to identify these across all assets in all departments revealed some interesting findings:

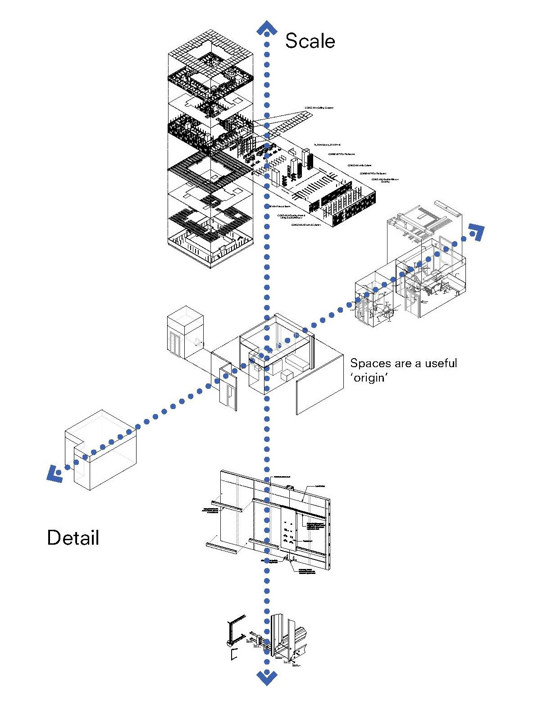

Fig.2 Spaces are useful ‘origin’ point in considering the size and complexity of built assets

Space type

Obviously, the department-specific toilet names are useful and meaningful (accessible, unisex, male, female, staff or visitor toilets can be worth distinguishing, for instance) so there is a level of granularity that shouldn’t be replaced. But it is clear why having 104 different names for one classification makes it nearly impossible to ‘harmonise, digitise and rationalise’ demand.

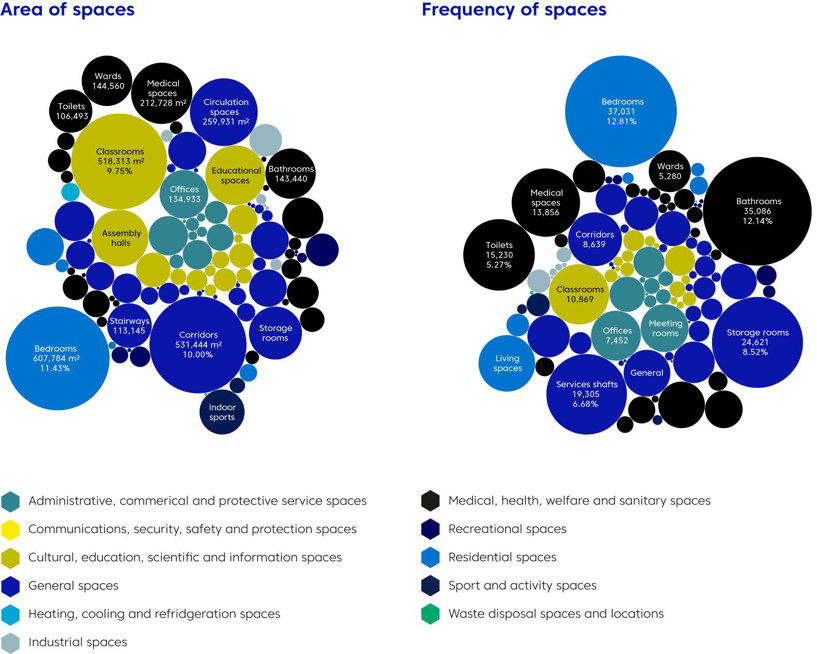

Once we have a common classification, it becomes straightforward to compare departments and identify areas of harmony. Being able to consider spaces across the estate by frequency and area, for instance, reveals something about the composition of a Platform solution.

High-frequency spaces are obviously of interest if we are seeking solutions that will have the greatest applicability. Within these, small spaces may facilitate a different form of delivery (say volumetric pods or ‘flat pack’ panels) compared to large spaces (where a more componentised approach may be more appropriate).

Fig.3 All spaces showing overall area (left) and frequency (right)

As we enter the next phase of work, the team developing Platform concepts will use this to seek those areas where a set of sub-assemblies will have the greatest impact in addressing the market need, while deeper analysis of the data will show the likely level of standardisation (one single solutions vs. a range of mass customisable solutions) that will be needed.

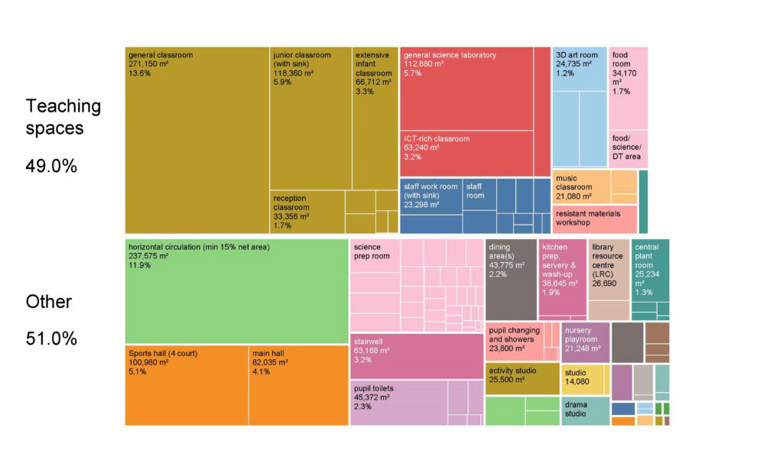

Assessing spaces by usage not department

With a common language established, we could separate out those spaces that form the core functionality of an asset (e.g. teaching spaces in a school, clinical spaces in a hospital) from the more generic spaces that are common across department spaces. Again, the results are telling.

Departments are not as ‘departmental’ as we first thought. The data shows that less than 50% of most departments’ spaces are truly specific to their sector. The majority are either ‘functional’ (i.e. only temporarily occupied, say) spaces such as corridors and circulation, changing, sanitary accommodation, storage and plant, or ancillary functions such as waiting areas, dining, gyms, studios and workshops. (The exception to this is the residential sector, which is more homogenous. However, this sector also has some interesting features which are described later.)

Circulation and corridors on their own account for 16% by area of all assets.

Fig.4 Spatial analysis across Department for Education pipeline

Fig.5 Spatial analysis across Department for Health & Social Care pipeline

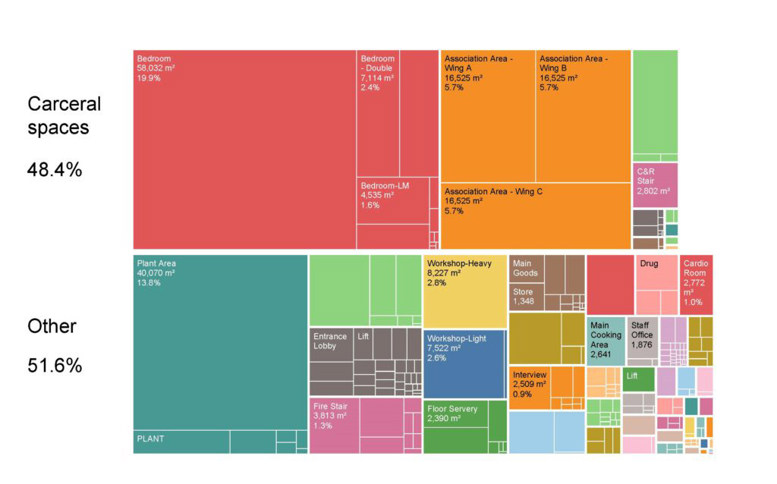

Fig.6 Spatial analysis across the Ministry of Justice pipeline

Working through the detailed implications of this is part of the next phase of work – platform concepting. But already, it shows the potential for creating high levels of repeatability and manufacturing efficiency, then deploying these at scale, for the spaces that are not core to an asset’s functionality. Meanwhile, departments can focus their time and effort on rationalising and optimising those spaces which are most critical to them.

So, a school of the (near) future could comprise teaching clusters which have been refined and improved by the Department for Education, linked together with a range of cross-sector, standardised corridor space types which have been similarly designed and optimised centrally.

Finding the degree of commonality in key spatial dimensions

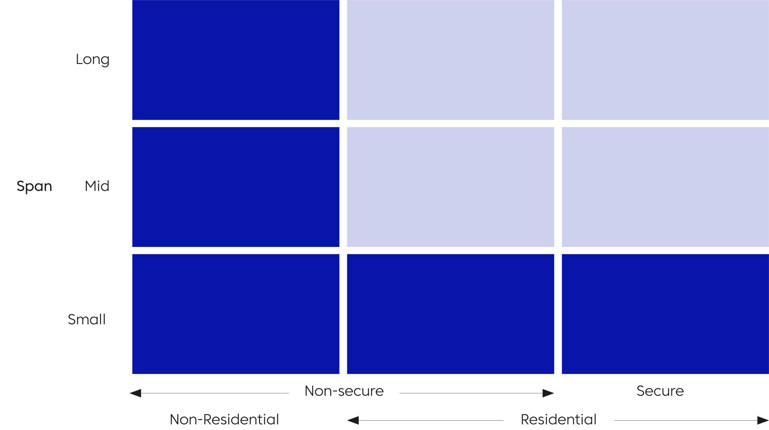

As well as analysing spatial functions, the team were looking at technical requirements. While there are nearly 80 different criteria (grouped under: geometry, visual, thermal, air quality, acoustic, vibration, functional, fire, robustness and security) one that showed itself to be fundamental is: span.

The ‘Delivery Platforms’ strategy document speculated on the number of platform types that would be needed (this suggested three: for ‘small’, ‘medium’ and ‘large’ span spaces), and the Hub’s ‘hypothesis specification’ suggested the form that would have the greatest overall applicability. The data has shown that there is indeed a set of characteristics which are highly common.

For instance, 70% of Government pipeline could be deployed using a mid-span (~8m) Platform. This shouldn’t really be a surprise; ceiling heights are based on human height regardless of sector, and this allows natural daylight about 8m into a building. This is why classrooms, healthcare wards, apartments etc. all have about an 8m depth.

However, having the evidence that we could create a very narrow set of structural requirements that would be applicable to 70% of the future pipeline is a phenomenal result. It is likely that there will be a range of systems in a mix of materials to meet this need, but this metric shows that there is a big enough market to support them all.

This is further supported by the report, which identifies the addressable and obtainable market for the system that the Hub is developing to demonstrate the application of this approach could fulfil circa 30% of the Government’s new build portfolio that was analysed. That is in excess of £13 billion over five years.

Revisiting the opening statement regarding consistency and certainty, and Construction Playbook policy around aggregating and rationalising demand, it is exciting to see that we are already starting to see how we can achieve this.

Residential will be a key market for platforms

Due to its current procurement routes, the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) was not originally listed in the Autumn Statement 2017 as one of the key departments that would be driving adoption of modern methods of construction (MMC). So perhaps a more surprising detail has been quite how prominently residential spaces have featured in the data set.

The Hub considered only a small proportion of the overall housing market for our data set. We excluded all private sector housing to just leave Local Authority and Housing Association housing, we then only assumed that flats, not houses, are in scope. What’s left is just 6.5% of the housing market. However, it is still a significantly larger area than any other department. Indeed, it is bigger than Education and Health combined. (This blog provides more detail on the residential sector analysis.)

When we then see that ‘residential’ also includes not just homes but also secure accommodation for the Ministry of Justice and single and family accommodation for the Ministry of Defence, the overall need is vast. Bedrooms and bedroom-studies account for 18.65% by area, and 15.72% by frequency, of spaces. ‘Residential spaces’ account for 38% of the total area analysed.

Whereas the Delivery Platforms document hypothesised the need for three platform types, the ‘Defining the Need’ report proposes a total of five, of which two are uniquely residential:

Fig.7 Diagram showing 5 potential platform solutions

More than any other application, this has the greatest opportunity to be taken up by the private sector. If the platform solution demonstrates how we can deliver ‘more beautiful, more sustainable, better quality homes in all parts of the country,’ then this could potentially be used to deliver private sector homes, student accommodation, hotels etc. The market in the UK alone is significant, but there is no reason to suggest we could not create a scalable solution to a global problem.

Conclusion – the data will continue to clarify the solution

The ‘Defining the Need’ work has shown the power of adopting an objective, evidenced-based approach to understanding the public sector estate. While the results are in themselves very useful, the process of gathering and analysing the data has itself proven to be a highly valuable exercise.

As the Hub’s work progresses, we will continue to strengthen and expand this data set, using it to guide the design and validation of our programme’s platform sub-assemblies. This will become a Kit of Parts; the components of the platform (sharing similar features, functionality or lineage) that can be varied within certain constraints.

The creation of a Rulebook – which will detail the rules and standards of how platforms are developed, the approaches and process to be applied and how technologies and sub-assemblies can and will be integrated – will be the enabling guide for wider adoption and deployment of these systems.

In the longer term, this work is a useful proof of concept as to how we can harmonise, digitise and rationalise demand moving forwards. And this in turn will be a key enabler of the shift that construction needs to make with evolving understanding of how platform solutions necessitate a change in organisational structures and toolsets to enable potential benefits to be unlocked.

Jaimie Johnston is the Hub’s Platform Design Lead and Director & Head of Global Systems at Bryden Wood. He was the author of the strategy documents ‘Delivery Platforms for Government Assets: Creating a Marketplace for Manufactured Spaces’, ‘Platforms: Bridging the gap between construction + manufacturing’ and ‘Data Driven Infrastructure: From digital tools to manufactured components.’ These were adopted as a key articulation of the Government’s aspiration to adopt a more manufacturing-led approach to construction, reflected in the Infrastructure and Project Authority’s proposed adoption of a Platform approach to Design for Manufacture and Assembly. Rebecca Wade is Bid Director for Kier’s large-scale projects division. She has cultivated a passion for DfMA and its application to project delivery, most-recently as a key member of the team delivering the multi-award winning HMP Five Wells.

Both Kier and Bryden Wood are delivery partner companies working on the Construction Innovation Hub.